Fair Trial

It’s that time of year again…time to use the blog for a little exam review!

If you haven’t seen My Cousin Vinny…you must. immediately.

As the title suggests, I’m going to talk about my Fair Trial course today. It’s a Sixth Amendment course, and focuses on the jury as a central protection for both accused criminals and democracy as a whole.

For anyone who’s ever served on, or will serve on, a jury - no pressure 😬

The overarching question is “What does ‘impartial jury’ mean in a world of power imbalances, structural inequities, and implicit biases?” Bottom line: there’s no such thing as a fair & impartial trial, so we just try to get as close as we can.

THE SIXTH AMENDMENT

The Sixth Amendment, ratified in 1791, reads as follows:

“In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence.”

You’ve probably heard of the 6th A protections in more “normal” terms - I know I have. I’ll run through the familiar ones quick:

SPEEDY TRIAL - can’t accuse someone of a crime and keep them waiting around forever! Each state has their own rules and timelines for fair trial, and the federal government’s rules are found in the Speedy Trial Act of 1974.

PUBLIC TRIAL - no secret-squirrel, Spanish Inquisition nonsense here. The theory behind this clause is that if the public is involved, the courts & government are held accountable.

JURY TRIAL - for (almost) all criminal prosecutions, an accused person has the right to have a jury decide if they’re guilty or innocent.

RIGHT TO BE TOLD ABOUT THE ACCUSATION - like #1, the government HAS to tell you what they’re charging you with. Sounds ridiculous but again…England seriously messed some stuff up…

RIGHT TO CONFRONT THE WITNESSES AGAINST YOU - this one’s tricky and we’ve spent a lot of class time discussing it. Originally, the confrontation clause was a SUFFICIENCY guarantee - are there enough live witnesses to establish that the accused might have committed the crime? Now, the confrontation clause is regarded as the accused’s right to confront the accusers - are the witnesses in court where the accused can cross-examine them? And never mind if there’s enough live witness testimony to ACTUALLY establish guilt…

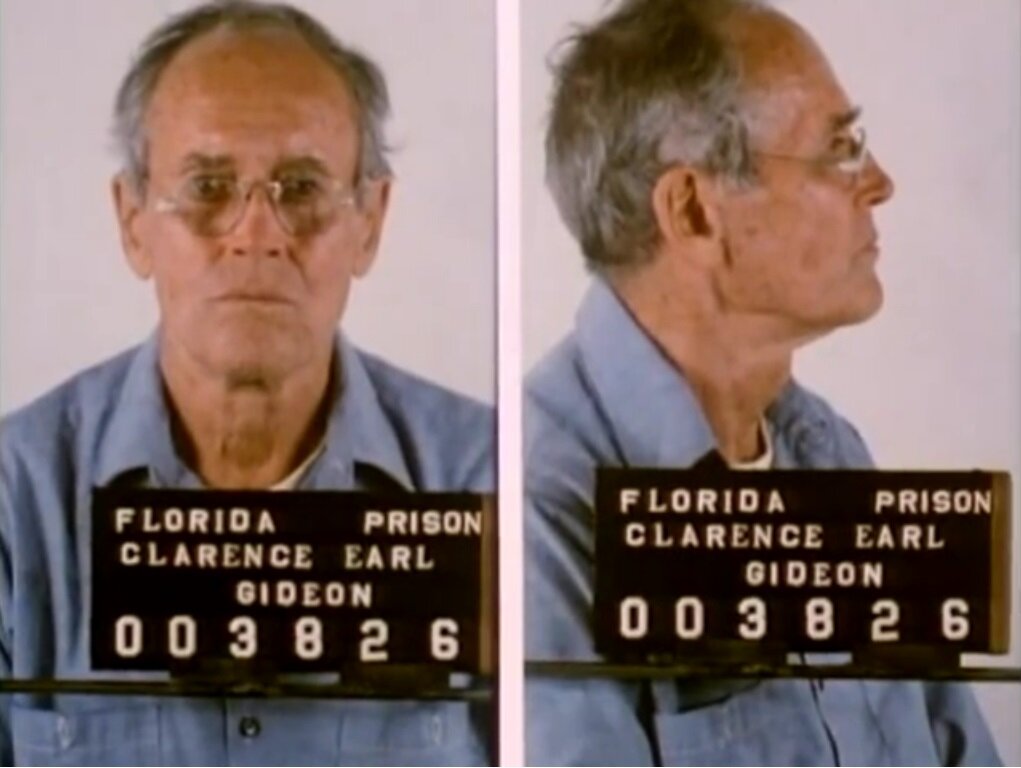

RIGHT TO A LAWYER - fun fact, you didn’t always have this! A 1963 Supreme Court case called Gideon v. Wainwright established that yes, the Sixth Amendment requires states to provide criminal defendants with a lawyer if they can’t afford their own. I HIGHLY recommend watching the movie Gideon’s Trumpet if you haven’t seen it!

TOPICS EXPLORED

As you can imagine, there’s a LOT to talk about re: Sixth Amendment. In the beginning of the course, we traced the development of the jury from America’s earliest days (and even before - we totally ripped off England’s system). We discussed the different types of legal framing, done by individuals, judges, and the words of the Constitution, and the natural power imbalance between judge and jury. We talked about what “beyond a reasonable doubt” means; the implications/use of jury nullification (where the jury says “we think this guy is guilty, but the law is unfair so we’re going to render a verdict of not guilty” - super interesting, you can read more about it here); the role of the grand jury; the Confrontation Clause x a mil; cross examination; jury selection; and criminal contempt (aka, when a judge says “you’re being insolent, here’s a fine and/or jail time).

My professor has taken a pretty unconventional approach to teaching Fair Trial, even for a Zoom class. He focuses far more on small group discussion and provoking thought experiments than analyzing cases and memorizing the current state of the law. Sometimes it gets confusing; we tend to jump around on topics, and occasionally I find myself wondering what the heck we just learned after class. But the course has posed a ton of interesting questions and challenges that I will carry into my work as an Air Force trial lawyer.

He also uses an anonymous space called Threads, where we have conversations without knowing who says what. I like Threads because it elicits a wider range of perspectives than a classroom environment - it’s difficult to openly go against the Harvard masses.

The final exam is just as unconventional as the class. It’s part essay, part timed exam, and both sections are VERY open-ended with VERY strict word counts. People are already stressing about it (but that’s pretty standard) and I confess, I need to brush up on more than a few topics!

COMMANDMENTS OF CROSS-EXAMINATION

I don’t want to hit you with my half-baked thoughts on the topics above, so I’ll end on a HILARIOUS video we watched for last week. It’s Irving Younger’s Ten Commandments of Cross-Examination and if you have ten minutes, please give it a watch.

Younger, a brilliant American lawyer, PROMISES that you “won’t be a buffoon in the courtroom” if you follow these ten rules:

BE BRIEF. This is NOT the Battle of Normandy, get IN and get OUT!

SHORT QUESTIONS, PLAIN WORDS. Everything they stamp out of you in law school…

NEVER NEVER NEVER ASK ANYTHING BUT A LEADING QUESTION! Control the witness and the conversation by putting words in the witness’s mouth. Yup.

ONLY ASK QUESTIONS TO WHICH YOU ALREADY KNOW THE ANSWER. Remember OJ’s glove??? Enough said.

LISTEN TO THE WITNESS’S ANSWER. And for goodness sake, be READY for the crazy answers!

DON’T QUARREL WITH THE WITNESS! Sit down when their answer is ridiculous - the jury will get it. Also, it is “unaesthetic” to fight with them.

DON’T LET WITNESS REPEAT WHAT HE SAID ON DIRECT EXAMINATION. Why? If the jury hears it once, they may or may not believe it; if they hear it twice, they’ll probably believe it; if they hear it three times they’ll CERTAINLY believe it and if it’s in writing, NOTHING ON THIS EARTH WILL PERSUADE THEM THAT IT’S NOT TRUE.

DON’T PERMIT THE WITNESS TO EXPLAIN ANYTHING. “Yes, no, I don’t know” - No “buts!”

AVOID ONE QUESTION TOO MANY. Difficult, because you always recognize one question too many after you’ve asked it…

SAVE THE POINT FOR SUMMATION! If the jury doesn’t remember, all the better - unsatisfied curiosity is the key to victory on closing statements.

Honestly, I’m still giggling - Younger is a true gem. And hopefully these commandments come in handy once I’m a ReAl LaWyEr!